A colorful Ochre Sea Star (Pisaster ochraceus) seeking a crevice in our rocky shoreline as the tide ebbs. The typical Ochre seastar here is Purple colored while most of their conspecifics on the outter coast are orange. This one has elements of both.

May and June are the best times to see our beaches and the denizens that live there as tides roll way out baring the near-shore sea bottom during daylight hours. These minus tides recede as far as - 3.54 feet below the mean tide level and rise to around 10 feet around here - a 13 foot sea level change. In shallow bays, such minus tides can bare a beach 100s of feet out from the shore that is totally covered during higher tides.

Low tide is for beach combing and foraging. Although we love our beaches, they are not like those in many other settings such as the outter coast (Pacific Coast) which has plenty of sand as well as rocks. Here they are largely rocky, pebbley and muddy, although some sandy beaches exist and are delights when we find them.

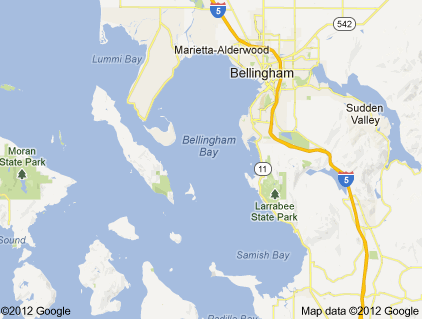

Map of Bellingham Bay. Islands to the left and bottom are the San Juan Islands. The beaches that we will visit are the following: Boulevard Park Beach is just below the “Bellingham”. The next beach mentioned is Little Squalicum and is just under the “Bellingham,” and the Lummi Shore Road Beach is on the peninsula directly across the Bay from “Bellingham”.

The Beach Topography

When the tides recede, the upper levels of the Intertidal zone are exposed to our view and to ready access without a snorkel or scuba gear. Some of the first sights we see as the tide ebbs are spent shellfish shells, (e.g., clams, mussels, and oysters), typcially strewn on the beaches after having been ravaged by local predetors such as racoons and shore birds.

Clinging to beach rocks we find anemonies and sea stars, like the Ochre Star in the lead photo. I will describe three of the many beaches around Bellingham Bay and then explore some of the near-shore sea critters that inhabit these same rocky and muddy tidelands.

Boulevard Park Beach

Although the walking trestle is relatively new many of the remenants on this beach are not. This is the site of the once, world’s largest salmon cannery. The dark rock-looking object seen in the upper center is actually a pile of old rusted tin scraps from the fish canning days over over 100 years ago.

Below shows the same area at high tide. There is little beach at all.

Boulevard tressle stretching over the water here connects to other shoreline trails and is a very popular with walkers, runners and bikers year around. At high tide, the water is nearly up to the walkway.

This photo of the Golden Ears peaks was taken from the over-water walkway in the winter. The peaks are in the British Columbia’s Golden Ears Provincial Park. The photo makes it look closer due to the telescopic lens used.

The next beach is just to the left of the photo above which is the North side of the Bay.

Little Squalicum Beach

This beach, like the one above, remains in the process restoration from the gross abuses of our fish processing and lumber exporting past. You see the long tressle going out into the bay. With the shallow water, ships could not get closer to load their piscatory cargo. The tressle has recently been renovated and made safe for the public to meander out on.

With the tide out, the mud flat looks like water but it is solid enough to walk on and the dogs love it as seen below.

In the background are some of the San Juan Islands. Orcas Island is the larger one in the background and Lummi Island is the flatter one. Between the two islands lies Rosario Strait.

Although there are few people sun bathing on this muddy beach, some still find a way to relax there.

Lummi Shore Road Beach

From this beach, one looks across the mud flats that are the delta of the Nooksack River that originates from runnoff and glacier melt on the north east side of Mt. Baker. It runs wild in the mountains and then slows and meanders as it approaches the bay carrying silt to form the muddy beaches.

This view is from the west side of the bay on the Lummi Indian Reservation, to the right of the previous photo. The beach composition here is pretty much the same as the other beaches that lay across the bay like the first two shown. Just about anywhere on the beaches you can see a Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) perched on a rock patiently awaiting its unsuspecting lunch to cruise by.

From this side of the bay, beach goers have a rather spectacular view to the east. Across the water is Bellingham’s South Hill, then the Cascade Mountains foothills and then Mt. Baker itself dominating the skyline to the east. It rises some 10,781 feet from sea level to its volcanic rim at the top. Although it is considered an active volcano, it hasn’t erupted in about 6,700 years. However, it spews out steam and gases from time to time but no eruption appears imminent.

Littoral (Intertidal) critters

This next section shows some of the more prevalent intertidal invertebrates we see here when the tide goes out.

Sea Stars

One of the advantages of having rocky beaches is that’s where the sea stars hang out.

Two Ochres becoming entangled. They are often found in piles.

Some species of Sea Stars are becoming relatively more plentiful after a serious die-off all along the Pacific Coast from Baja to Alaska lasting from 2013 to the present. Stars like the Ochres have made a significant recovery, although not yet back to pre-epidemic levels. Other species have not fared as well. The cause(s) of the disease called Sea Star Wasting Disease, (SSWD) are as yet unclear despite ongoing research. Warming waters is thought to be one of the contributing factors.

Here a diseased sea star on Boulevard Park Beach is in the process of losing a second arm- they should have five. I think the species will survive this waning epidemic as they have for so many eons while so many other taxons have faded from the palaeontologic record.

Starfish have almost always had the same five-armed body shape. The five arms remain the norm which has not changed for almost 480 million years,

However, there are species that have up to 40 and more arms like the Sunflower star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) shown below which has 20.

Some species are making a comeback. Others sadly, have not rebounded such as the magnificient and colorful Sunflower stars that grow up to three feet across.

Sunflower Sea star image from Oregon State University (College of Science). There was nearly a 90% die-off of these colorful critters along the west coast and 100% in many california ecosystems. A few appear to returning in a some areas.

Sea stars’ importance to the well-being of the near shore habitat becomes clear when they suddenly disappear. As a critical element of an established food-web is extracted from an ecosystem, especially a keystone species like sea stars, the system becomes out of balance. The loss of seastars allowed one of their favorite food sources to flourish like the Spiney Urchins whose food source is Bull Kelp. With the predetor urchin unchecked, kelp forests have dwindled and many have disappesared leading to the loss of an important eco-system for numerous fish species and even whales who hang out in these undersea forests to protect them from large storms along the coast.

The Ochres and some others continue to bounce back around here. Below is a group of very young stars, all of which were born after the epidemic began. Such groups of young stars give us hope that they will fully recvover their previous numbers.

A cluster of young Ochres and one Mottled Star (Evasterias troschelii). For more information about this engimatic sea star wasting disease, check here and here for some of my previous writings on another site.

Dungeness Crab (Cancer magister, Metacarcinus magister)

Although I am clearly partial, I do believe that Dungeness Crab are the most delicious crab found in our seven seas. The main thing I miss about boating out among the San Juan Islands and right here in Bellingham Bay is catching and eating these crabs. Damn they are good!

Here are four legally caught males posing for the camera on the beach strewn with clam and oyster shells. You can see barnacles on the oyster shells at the bottom left. And in case you haven’t heard, the Dungeness crab is tastiest of crabs, purely delightful when cooked and eaten fresh from the salt water. Although most often fished off shore with crab pots, at very low tides they can be found huddled in the eel grass to keep damp until the tide comes back in.

An eel grass bed ar Boulevard Park Beach - the crabs prefered hangout.

A Red Rock Crab (Cancer productus) These are plentiful here as well as the Dungeness, although they are less desireable for the table.

A common site on our beaches in the spring is recently molted Dungeness crab carapaces. Crabs molt, (shed their carapace) in the spring and are off limits for fishing until into July when their new shells harden. Female Dungeness crabs like the one above, are are always off limits for either sport or commercial fishing.

Oysters:

Another culinary delight from our local shores are oysters of several species. Many are cultivated in local waters even though they are not native, they are delicious. They are quite literally spread about the beaches, attached to just about any hard surface including other oysters. In season one is allowed 18 per day. To preserve their prefered substrates, they must be shucked on the beach and the shells left.

A significant caveat to this story of a seeming oyster paradise is that one must be very selective in choosing your beach becasue many are closed to shellfishing during the summer months. Closures are due to the presence of water-borne toxic pollutants and pathogens that cause Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP). At this writing, all beaches north of Bellingham Bay are closed up to the Canadian border due to high levels of PSP.

Oysters aplenty at Boulevard Park beach.

More oysters on the beach and one really fat one opened up. I did not eat this one due to PSP.

And if non-toxic, they are a delight fresh from the water to the grill with butter and a tad of garlic. I bought these from an oyster farm.

Taylor Seafoods oyster farm at low tide. Same place, at high tide.

This oyster farm is technically set in Skagit Bay that is essentially a southern extension of Bellingham Bay, as seen on the map. What looks like a grape vinyard on the left are rows of cables covered in seaweed to which bags of oyster seed are attached. The bags rise and fall with the tides tumbling the oysters which is said to strengthen them as the grow.

This and other oyster farms close, as do public beaches, when the PCP levels reach a certain level. I will trust the State Health Department as just this morning I bought a bag of “Fat Bastard” oysters from this farm. If you are reading this, I lucked out and they were safe.

So, this was an introduction to our local beaches and some of the critters that reside there. The second part of this post will cover some of the vertibrate inhabitants that make their living and inhabit the beaches of Bellingham Bay.

See you soon.