Chuckanut Creek is a prototypical salmon-spawning creek about 2.5 miles from my home yet within the city limits. This Creek is fed by runoff from its namesake, Chuckanut Mountain and runs about 6 miles before emptying into Bellingham Bay.

During the late summer and through fall, most Pacific Northwest (PNW) salmon return to their native streams to spawn. Watching salmon working themselves upstream is a festive and educational event around here. There are many salmon-watching groups in our area including school classes, led by various environmental organizations. One of my favorite fall activities is checking out the salmon streams to observe this millennia-old ritual play out yet again. Sometimes while searching for salmon, I do my other favorite fall outdoor activity of hunting mushrooms, as I illustrated in my previous post.

The spawning behavior we observe here is the culmination of a several years’ long process that starts with small eggs laid in a stream bed, maturation and physiological changes (smolting), travel to the open ocean for as much as 1,000 miles or more, feeding and gaining bulk, returning to native streams, making a nest “redd”, and laying their eggs. And then it all starts over. I will describe and illustrate these various processes.

The Species:

There are five species of salmon that spawn in the Pacific Northwest streams and all five are found in the waters flowing through Bellingham, Washington’s five creeks. These five spawning creeks drain from the surrounding hills and flow through town and into Bellingham Bay. Fortunately for us, they are all quite accessible for viewing.

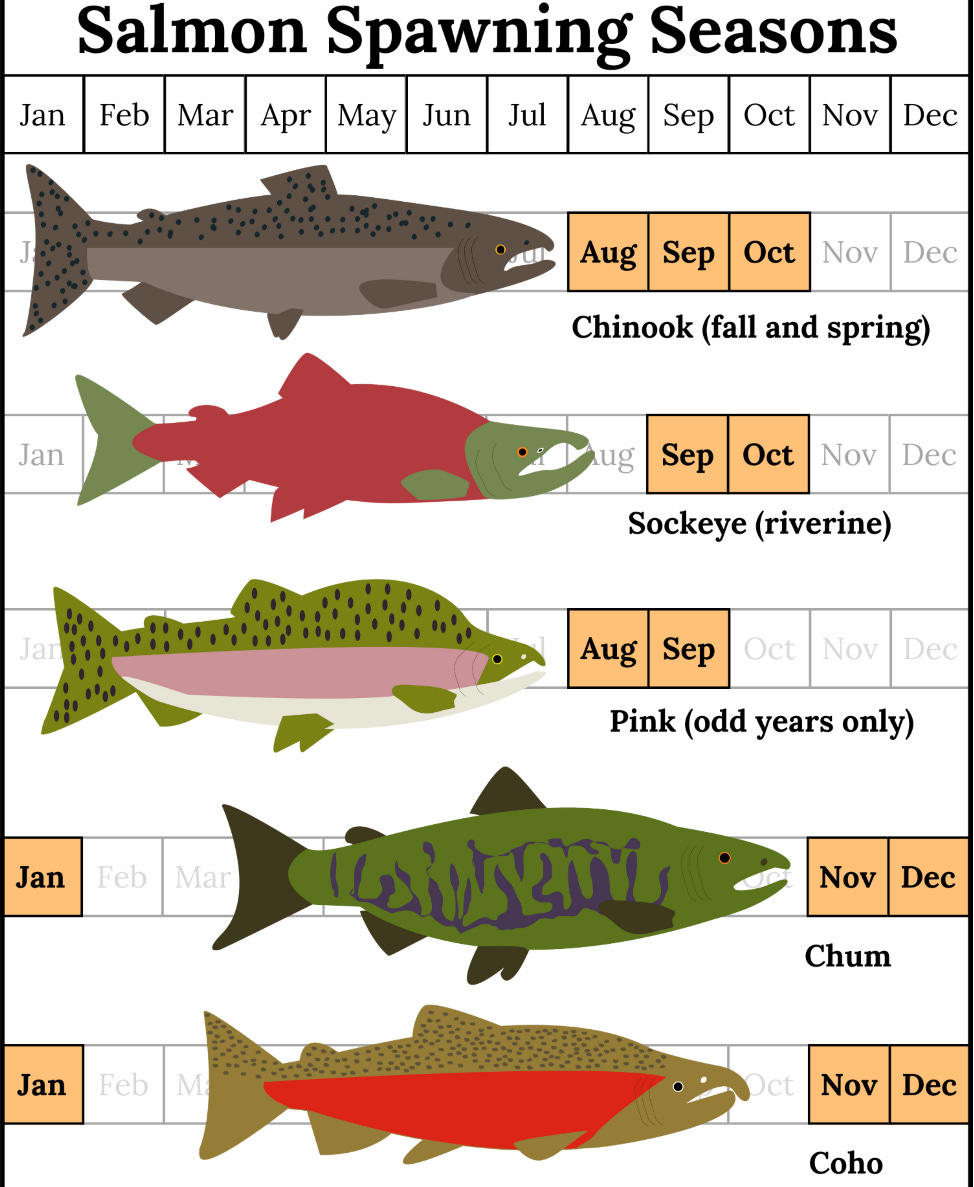

The fact that the species have different maturation and spawning schedules opens up a wide window for observing them from late summer to early winter. For example, Pink Salmon (pinks, or humpies) return to spawn in August and September whereas Chum and Coho return from November to January. Further, Pinks return to spawn after only two years at sea while the rest are mostly on a four-year cycle although some are as long as seven years.

Below is a graphic showing the five species with their usual spawning times and their spawning colors. While at sea, they all have shiny, silvery-colored scales. However, when they return, they change their colors as seen in the chart. This change serves to identify their species such that mates will be attracted to them, but not to another species, similar to how birds change colors during mating season. Not only do they change color when heading home to spawn, but they typically stop eating when they reach their home stream, having acquired enough fat and bulk to get them upstream and to spawn.

PNW salmon in their spawning colors and their spawning timetables

Early Development and off to sea:

The eggs hatch after about 6 to 20 weeks time in the redd depending on species and water conditions. Once hatched, they go through several stages of development. First they start developing bodies that have an attached egg sac that provides them nutrients until they can feed themselves.

Salmon eggs starting to hatch. The three in this photo that have hatched carry an egg sack under them that nourishes them until they can feed on their own.

As they continue to develop as salmon, the little fish, now called “alevins” spend several months in their creek growing and learning to feed themselves. Once they can survive on their own they become “fry” as shown in the photo below in a cool shaded pool. To survive they require clear, cool, uncontaminated and calm pools of water. This is why they need streams with plenty of overhanging vegetation to shade the water from the sun like the one shown in the lead photo. ( You have probably figured out that climate change, water pollution, and deforestation, among other things, are serious threats to the survival of natural or wild salmon.)

Small salmon fry swimming about in the cool clear water of their native creek

As the fry develop and grow, they begin finding their way downstream to where the freshwater mingles with the saltwater of the ocean, creating an “estuary.” Here, in the brackish, half salt and half fresh water, their bodies undergo physiological changes that allow them to live in saltwater. This adaptation process is called “smolting,” and the fish at this stage are called “smolts.”

Once adapted, up to several months, they are ready to begin the next leg of their journey. Now they head out into the cold and bountiful waters of the Northern Pacific Ocean. There, they feed in the nutrient-rich waters to fatten up and prepare for their eventual homeward return to their native streams where they will spawn the next generation.

After further growth and maturation at sea, in this case, the North Pacific along the Aleutian archipelago of Alaska, their “time to go home” genes kick in and they head homeward. At this time they could be as much as a 1,000 miles from their native stream. Further, there are literally many hundreds of spawning streams along the way but they must find the one in which they were spawned. How do they find their way home? Well, like many of us, they travel by compass. Theirs however is built in. The salmon are guided by geomagnetic fields that point them toward their original stream location, directing them on their final journey.

In the words of Nathan Putman, a salmon researcher at Oregon State University: “… salmon remember the magnetic field where they enter the ocean and come back to that same spot once they reach maturity."

The magnetic cues get them close but as they approach their natal stream, it is thought that their sense of smell (memory) guides them directly to their specific stream.

The final struggle

Once they arrive at the home stream, they must move upstream until they find an appropriate spot to dig their redd and lay their eggs. Depending on the location and type of stream, there can be obstacles in their way. First, having stopped eating, they have only their fat reserves for energy and strength. They might also encounter physical obstacles such as waterfalls and predators.

Potential hazards to salmon heading upstream to spawn. (Credits, Salmon jumping falls, Wikipedia, and Grizzly bear eating salmon, Getty Images)

I found this pile of salmon eggs alongside Chuckanut Creek - clearly not in a redd. A predator apparently pulled her out of the stream before she spawned and hauled her body off, leaving the eggs along the shore.

Still many elude these hazards and survive to pursue their destiny. If successful, they are free to continue upstream until they find an acceptable place to dig their redd and spawn.

Below are some photos and video clips taken from our local salmon spawning creeks, illustrating this last part of the journey,

A short snip of one salmon moving upstream

Exploring the bottom looking for a good spot to dig a redd?

A female salmon digging her redd with her tail by pushing rocks aside.

The aftermath of the spawn.

A clip of a spawned-out salmon that died and is being swept downstream.

Two dead spawners having washed up along the shore

A Salmon’s afterlife

Seeing spawned-out, dead salmon strewed along the shore or floating downstream, it seems their usefulness is over. But it is not. Their contributions to the ecology of their stream and the adjacent forest continue. I noted previously that predators are a danger to salmon when they return to spawn. However, their desiccating bodies still contain significant nutrients that are critical to the health of the stream and the surrounding flora. Those bodies that deteriorate in the stream provide nutrients for the insects and benthic organisms on which the salmon fry will feed after they hatch. Predators that drag them from the shore and feed on them also gain nutrition. Finally, the fish carcasses left by the predators on the forest floor nourish the trees and und understorage shrubbery that will continue to shade the stream and keep it cool for the subsequent generations.

Thus the Salmon’s stages of life come full circle with their death. However, their contribution to sustaining the environment as well as their species continues even beyond their lives.

My next post picks up where this one ends and finds me in the Nooksack River Valley that runs through the foothills of the Cascade Mountains to Bellingham Bay. It is January and the salmon spawning in our local streams and rivers is coming to a close. It is time to head up the Nooksack River to watch the Bald Eagles perched high in the trees along the river, scanning the shore for salmon carcasses and gorging themselves when they spot one.

Stay tuned for a Bald Eagle binge, and subscribe if you haven’t already.

Thanks Mike,

It is good to hear from you and I am pleased that you enjoyed the post.

Salmon are indeed still a bit of a mystery but most agree they sure taste great. We do have to be sure not to overly abuse them.

If you haven't already, you might also enjoy reading my previous post on Mushrooming this past fall.

https://rasklein.substack.com/p/its-mushroom-season-in-the-pacific

This is a wonderful post about the life of Salmon. I too am a PNW resident (just arrived) and I am endlessly amazed with the nature here. It's great to find some other folks writing about the area! I look forward to reading your words. One thing I discovered recently was about the connection of bears, trees and salmon. As an engineer I see this as the ultimate circular economy and I wrote about this recently here https://open.substack.com/pub/waterboy1/p/the-salmon-bear-forest-connection?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=4fmtbn